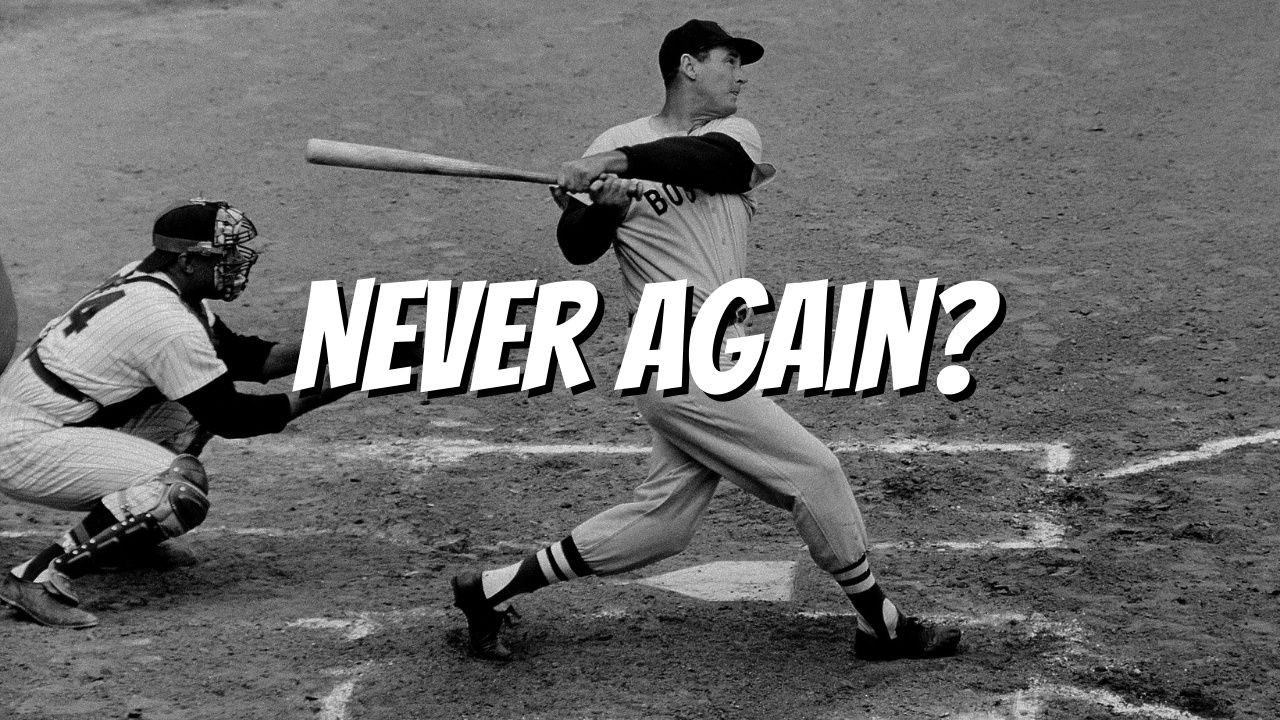

Shrinking Alpha: Will Outperforming the Market Become as Rare as a .400 Batting Average?

Why is Ted Williams the only baseball hitter to surpass the .400 mark?

Ted Williams was an elite hitter, but he also played during an era when the dispersion of talent was far greater than it is today. This environment allowed for extreme performance outliers like his.

During Ted's playing years, the gap in batting averages between the best and worst hitters was significantly wider than it is in modern baseball.

The chart below, from Michael Mauboussin's book The Success Equation, illustrates this phenomenon using standard deviation and the Coefficient of Variation.

Variance is simply standard deviation squared, so a reduction in standard deviation corresponds to a reduction in variance. The coefficient of variation is the standard deviation divided by the average of all the hitters, which provides an effective measure of how scattered the batting averages of the individual players are from the league average. The figure shows that batting averages have converged over the decades.

Mauboussin, Michael J.. The Success Equation: Untangling Skill and Luck in Business, Sports, and Investing (p. 55).

Also, the gap between the best and worst pitchers was substantial. Ted capitalized on pitchers whose skill levels were far below his own as a hitter.

The dynamic between pitching and hitting in baseball resembles the classic predator-prey model. It's an ongoing battle of adaptation—each side adjusting to the other's strategy, knowing that success hinges on outperforming the opponent. As both sides continuously hone their skills, the overall dispersion of talent gradually narrows over time.

Another significant factor contributing to the wide talent dispersion during Ted's era was the artificially limited MLB talent pool. Ted's .406 season occurred in 1941, six years before Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in professional baseball in 1947. Today, the talent pool is open to all, with only the most skilled players making it to the highest level, regardless of skin color or nationality.

This decreasing dispersion of talent has made extreme performance outliers like Ted Williams' .406 batting average highly improbable. It's unlikely we'll ever witness another .400-plus hitter in Major League Baseball.

Similarly, in active money management, we're witnessing a compression of performance disparities.

The skill level of active managers has increased year after year, mirroring the trend seen in Major League Baseball hitters. The widespread access to information and democratization of knowledge, coupled with technological advancements, have raised the performance bar for everyone in the field.

Furthermore, the talent pool of active managers has expanded significantly over the years as social and physical barriers to entry have diminished. Today, the most talented and ambitious individuals can compete in the financial arena, regardless of their background or location.

Competition matters.

— Frederik Gieschen (@FrederikNeckar) September 22, 2024

"When we were young, we had way less competition than you people have now. There weren’t very many smart people in the investment management field.

Now we’ve got armies of brilliant young people." pic.twitter.com/uYoQ1KqKvA

Active management faces another factor shrinking the dispersion of talent: indexing.

Unlike in baseball, where less talented players simply exit the field, underperforming active managers can pivot to low-cost indexing strategies. This shift intensifies the pressure on remaining active managers to outperform and justify their higher fees.

Some would argue that the growth of index funds makes markets more inefficient, as index investing is little more than a version of lagged momentum (index trackers add to shares which have done well and sell shares which have done badly). The alternative argument is that the growth of indexation is coming at the expense of weaker active managers. The best analogy is a poker game where the poorer players lose their money and drop out first. Arguably, that makes the game harder for the more skilled players that remain, not easier. - Marshall, Paul. 10½ Lessons from Experience

Indexing strategies are becoming increasingly sophisticated, distilling complex active strategies into just one or two factors. This evolution is intensifying the pressure on active managers to outperform their benchmarks.

The overall long-term track record for active funds is subpar. About 29% of them survived and beat their average indexed peer over the decade through June 2024. Success rates were generally higher among foreign-stock, real estate, and bond funds and lowest among US large-cap strategies. - Morningstar’s US Active/Passive Barometer September 2024

Unlike baseball's relatively small and controlled field, the vast financial world still allows for performance outliers to emerge. However, this may not last indefinitely. As indexing gains popularity, at what point will it become increasingly difficult for active managers to outperform the market over the long term? Moreover, what new benchmarks for exceptional performance might arise in this evolving landscape?